Over at The Money Illusion, Scott Sumner, an Economist with a PhD in economics from the U. of Chicago recently posted an entry with the title: America’s amazing success since 1980: Why Krugman is wrong.

His thesis is that neoliberal economic policies promote economic growth, and further, that a country's growth rate relative to other countries is a direct result of having or not having employed neoliberal policies.

I am about to deconstruct Sumner's methodology and eviscerate his conclusions. First, though, a disclaimer. I am not an economist. I do not speak the jargon, and am unfamiliar with many of the concepts. However, I have a technical background, two masters degrees (Chemistry and an MBA) some proficiency in math, critical thinking skills, a finely-honed sense of skepticism, and the ability to graph data sets. Most importantly, I believe in data-driven conclusions, not conclusion-driven data mining.

Next, let's take note of the kerfuffle Mike Kimmel and Spencer over at Angry Bear got into with Sumner. This illustrates the hazard of getting into a point-counter point with someone who is ideology driven, especially after he has framed the debate in a way that is favorable to his conclusions. The thing to do, I'm convinced, is go after their basic assumptions, and refute them with actual facts. That will be my goal in this post.

Let's also take note of Sumner's sloppy methodology, and apparent lack of irony. He states:

Krugman makes the basic mistake of just looking at time series evidence, and only two data points: US growth before and after 1980.

It's fine with me if somebody disagrees with Krugman. Hell, it's fine with me if somebody disagrees with me. I do insist, though, that the disputant think clearly and make some sort of sense, if he's out to prove anyone wrong. Here, Sumner calls two time series, "two data points," when each series is - how else can you say it - a series. Then he goes on to draw global conclusions from three data points each for the several countries he deals with. These are three data points chosen from a series that contains 28. The best you can say about this is that it's lazy. It smacks of cherry picking. When I saw it, my bull shit alarm started flashing bright red.

The data series Sumner harvests is GDP/Capita PPP (purchasing power parity) from the World Bank There are several GDP series available from the WB, and other sources. Though I'm using a WB GDP/Cap PPP data series, I'm not certain the series I'm using is the same one that Sumner used, but there are certainly similarities. More on this later.

Sumner takes each country's GDP/Cap as a percentage of U.S. GDP/cap for 1980, 1994, and 2008. These are the beginning, middle, and end of the WB data series values. He reasons that if a country's GDP/Cap is increasing or decreasing relative to the U.S. - as indicated by how the ratio changes over time - that indicates how much better or worse their economic policies are compared to ours and other countries under consideration. His final answer is (with his empahasis):

So there you are, all these countries support my hypothesis that neoliberal reforms lead to faster growth in real income, relative to the unreformed alternative.

To which he adds in an update (emphasis added):

But I was primarily interested in international comparisons, for which all I had was GDP data in PPP terms. The point was that countries that did more reforms did better than those that did fewer reforms. I am not denying that growth in US living standards slowed after 1973, rather I am arguing that it would have slowed more had we not reformed our economy.

Neoliberal. in this context means the low tax, low regulation, free-market, pro-business, anti-union policies of Reagan and Thatcher. Philosophically, it also implies what G.W. Bush called "the ownership society" as he attempted to dismantle Social Security, and the replacement of public good or community ideals with those of individual responsibility.

Sumner presents a table including GDP/cap data for several countries as a fraction of U.S GDP/cap for his three selected years, then gives some text as to why these results confirm his idea that neoliberalism is superior to whatever it is that Krugman propounds.

This neatly finesses a number of issues:

GDP is a one-dimensional look at a country's economic performance. A time series gives you growth and growth rate, not much else.

GDP/cap relates to the mean income of a nation, and tells you nothing about how the income is distributed.

In the U.S wealth and income have been redistributed from the have-nots to the haves in dramatic fashion since 1980, and the disparity is now the greatest it has been since before the Great Depression. I suspect the same might true in Sumner's favored countries.

In the U.S. at least, since WW II poverty has increased whenever there was a Republican president, most dramatically during the Reagan and Bush II eras, and decreased whenever there was a Democrat in the White House.

GDP/cap isn't just a fraction, like cutting a pie into 8 equal slices. It is a ratio of two values that are not independent of each other. The nature of their dependence is complex and can well vary over time and between countries. Further, a times series of ratio values is influenced by changes in both the numerator and denominator. Consider two countries with identical GDP growth. Country A has high rates of live birth and immigration, and low rates of mortality and emigration. Country B has low rates of live birth and immigration, and high rates of mortality and emigration. Clearly, Country A is a better place to live, but over time, country B will outperform it in GDP/Cap because of relative population decline. Ratios are traps for the unwary.

The actual numbers that Sumner looks at are GDP/Cap for each country as a fraction of GDP/Cap for the U.S. This is a ratio of two ratios. We aren't quite at the level of angels dancing on pinheads yet, but this is a mathematical game at a high level of abstraction, with a relationship to reality that is, at best, tenuous.

And not least, both Reagan and Bush II inflated GDP by running enormous deficits, so their values are artificially large(in spite of which, Bush II has given us the lowest GDP growth since the Great Depression.) Clinton was pretty far right - he gave us NAFTA, welfare reform, and financial deregulation - but no neoliberal. I'm not a big Clinton fan, but he reduced poverty, raised taxes and balanced the budget. He will be a touchstone before this post is finished.

Reagan, in particular had at least some actual policies that are conceptually inconsistent with neoliberalism. As an example, he was the only president since WW II "who increased both the size of the national debt as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and the percentage of Americans employed by the federal government." (See Pg 2 of the intro, included with Chapter 1 at this link.)

Sumner's weak conceptual framework is further undermined his assumption that GDP growth is solely or primarily a function of the native degree of neoliberal policy implementation, ignoring business cycles, economic shocks, political unrest, imports, exports, inventory adjustments, and all other endogenous and exogenous factors that can come into play.

Let's agree on something before we get into the meat of the discussion. Since 1980, there have been two periods of nominally neoliberal economic policies in the U.S: 1) under Reagan (such as it was) from 1981 to 1989, and 2) under Bush II, from 2001 to 2008. The 12 year span encompassing Bush I and Clinton was a non-neoliberal interregnum.

Here is Sumner's table of each country's GDP/Cap, as a fraction of U.S GDP/Cap, along side my values for those same items. Both of us got our data from the World Bank. I am baffled by the differences, highlighted in red. I've ignored those with small differences in the third decimal place.

Our values for European countries differ. Some of these difference are pretty minor, some are pretty substantial. Make of it what you will. Our values for all other countries are either right on, or very close.

Sumner identifies countries that have done well and those who have done poorly over that 28 year span.

On the good side: the city-states of Hong Kong and Singapore, Great Britain (with Thatcher's neoliberalism), Australia, Canada, and Sweden, all of which introduced neoliberal reforms on or about 1994, Sumner tells us, and Chile, South America's primary neoliberal experiment.

The also-rans are Japan, France, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, and Argentina. See Sumner's post for details.

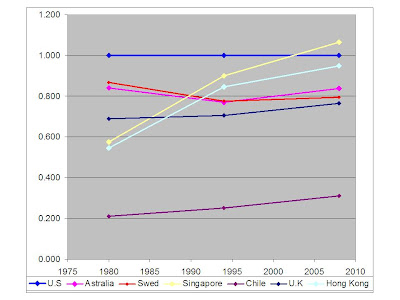

Looking at that table of numbers doesn't do much for me (after all, for many of these countries, decades of presumably good or bad policy have lead to changes in the second decimal place.) so I graphed them. First, Sumner's good guys, vs the U.S., pegged at 1.0. In this set of graphs, for European countries, where the data differ, I am using Sumner's numbers.

First easy observation: great gains by Singapore and HK, nice positive for Chile, so-so, at best, for the others.

Second easy observation: an inflection point at 1994 is a common feature, though not all bends go the same way. And where there is one bend, there could be two, or five, or seven, if we look at the entire data set.

Next, the bad guys.

First easy observation: Switzerland looks like the big loser here, Argentina holds its own after 1994, other changes are not particularly dramatic.

Do you see a lot there to hang your hat on? Frankly, for most of the countries considered, there's not much there, other than an inflection point. Again, for the majority of the countries considered, there is a difference in the second decimal place, after 28 (or 14) years of presumably definitive policy action.

As scant as this all appears, my approach is to look at the entire data series, not three isolated years, and see what picture that paints for us.

Let's look first at Sumner's good guys.

The red/blue line at 1.00 is U.S performance, of which the other country values are percentages. Yellow = Singapore, pale blue = Hon Kong, pink = Australia, Red =Sweden, dark blue = U.K. Same color code as above. I've place a few horizontal blue lines on the graph to indicate the duration of the Clinton administration. The Reagan years show two gains, two losses, and not a lot of change for the U.K. Trends during Clinton's time were flat or down. Everyone gained against Bush II

To get another - and frankly, more dramatic - look, I took a 5 Yr slope (rate of change) by simply subtracting from each year's value, that from 5 yrs earlier: ROC =Val (85) - Val (80), etc. Here is a graph of that data, same color code as above.

For Singapore and HK we see positive and increasing slopes during Reagan and Bush II, sharp declines during Clinton. Australia and Sweden have fairly constant, slightly negative slopes vs Reagan. Australia gains during Bush I, but starts to falter against Clinton. Sweden goes from negative to positive slope during Clinton's time.

Great Britain meanders along, mostly a little bit above the zero line. Well, they do have socialized medicine there. They all gain vs. Bush II.

Now, for Sumner's bad guys. Color coding same as above.

Not a lot of positive here - except during the late 80's - the latter part of the Reagan regime, when even laggard Italy showed some positive action. Note that the biggest declines are relative to the Clinton administration. These unreformed economies all gain against Bush Sr. and mostly hold their own against Bush Jr.

Let's look at the 5 Yr ROC.

Every country in the group had its best performance from about 1985 to 1991 , and it's worst performance during the Clinton era. After 2000, it's a bit of a tangle, with all slopes, except Italy's, reaching or approaching 0 by 2005.

We haven't yet taken a close look at Chile and Argentina. Their values are numerically similar, and far from those of other countries, so I've graphed them together.

Top two lines are the actual data points for Chile and Argentina, and the bottom two are ROC. We see Argentina in a steep decline during the 80's - a time of local political turmoil and economic uncertainty. Meanwhile, Chile is pretty flat relative to Reagan, and both countries take off against Bush I. They flatten and lose ground relative to Clinton. Both gain again vs Bush II, Argentina far more dramatically.

I just realized I left Canada out of the graphs. For the sake of completeness, here it is.

Pretty lame for a good guy. The values for 1994 and 1999 are identical at .816. The only gain is against Bush II, and it's not much.

Conclusions:

Remember, this whole line of reasoning is very highly suspect. Given that caveat, what Sumner would have us believe - that neoliberal reforms lead to superior performance vis-a-vis other countries, is the exact opposite of what this data tells us.

First off, most of the countries looked at ended up 28 years later at pretty close to where they started. How can you draw broad conclusions about policy when the results are trivial?

Second, the big gains came against both Bushs. Sr. had a major recession, while Jr. had a recession and more. He also gave us the lowest sustained level of GDP growth in the entire post WWII era. Endogenous U.S. factors during those times inflated the numbers of other countries.

Third, other countries' performances relative to Reagan are a mixed bag, with both gains and losses - mostly small - taking place during the span of his 8 years. Between 1985 and 1989 the poorest performing countries were either flat or showed small gains.

Fourth, nobody made a big gain vs Clinton. Those countries who lost vis-a-vis the U.S. lost the most during his presidency. Those countries who gained the most vis-a-vis the U.S. either flattened or declined after 1995. In fact, none of these countries gained at all against the U.S from 1995 to 1999. Coincidentally - or not - that is when neoliberal reforms were introduced in Australia, Canada, and Sweden.

So there you are, none of these countries support Sumner's hypothesis that neoliberal reforms lead to faster growth in real income, relative to the unreformed alternative.

The point is that countries that did more reforms are only vaguely distinguishable from than those that did fewer reforms, and their biggest gains came against U.S. recessions and Bush II's generally declining growth in GDP. I am emphasizing that growth in US living standards slowed after 1973, and I am arguing that a great deal of this slow down occurred because of Republican economic policies.

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://www.kitconet.com/charts/metals/gold/tny_au_xx_usoz_4.gif)

10 comments:

Hi there jazzbumpa. Lots to read through several time. Thanks.

Dan

Sorry for commenting on an old post, but one lengthy critique deserves another.

"Here, Sumner calls two time series, "two data points," when each series is - how else can you say it - a series."

True, but since we're just talking about one exogenous shock (nobody is referring to specific neoliberal reforms in each particular year), there's no additional statistical power from having additional points in a series. So I'd actually say Sumner is wrong in the opposite direction: the change in growth for one country should be thought of as one datapoint. Similarly, Sumner's three datapoints per country should also be thought of as just one (the difference between 2008 and 1980).

"It smacks of cherry picking"

Perhaps in his choice of countries, but not years. 2008 is of course the last year available, so he couldn't cherry-pick it. 1980 is conventionally used to date neoliberalism (that's how Krugman does it). 1994 is simply the midpoint and (I suggest above) irrelevant at any rate.

"He reasons that if a country's GDP/Cap is increasing or decreasing relative to the U.S. - as indicated by how the ratio changes over time - that indicates how much better or worse their economic policies are compared to ours and other countries under consideration."

That would be an incorrect conclusion, due to catch-up growth. But now I'm criticizing Sumner instead of you!

"Neoliberal. in this context means the low tax, low regulation, free-market, pro-business, anti-union policies of Reagan and Thatcher."

That's not quite how Sumner uses the term. He gives a definition in his "Great Danes" paper, where he says neoliberalism includes a large welfare state but little "statism". By that criteria, Denmark is the most neoliberal. So it does not imply the replacing Social Security with the "ownership society".

"GDP/cap relates to the mean income of a nation, and tells you nothing about how the income is distributed."

Krugman started by arguing about growth with reference to GDP, so Sumner was responding in kind. Sumner did have an update discussing distribution though.

"I suspect the same might true in Sumner's favored countries."

I don't know about the other countries, but Worthwhile Canadian Intiative has said Canada also has increasing inequality.

"GDP/cap isn't just a fraction, like cutting a pie into 8 equal slices. It is a ratio of two values that are not independent of each other."

Their dependence is precisely why people normally divide the former by the latter.

"over time, country B will outperform it in GDP/Cap because of relative population decline"

This might be an issue if there were an increasing fraction of non-working age population (children), but otherwise it would seem country A is getting poorer. If that's because low-wage immigrants are coming to get better jobs (which are still lower paying than average), it's no mark on country A, but if it's unable to provide as productive jobs for its own children that does indicate decline. So this would understate the policy benefits in countries with lots of low-skill immigration, such as the United States, and overstate that of a country like Japan.

"but no neoliberal"

What? He's the archetypal neoliberal pol in the United States. Self-described neoliberal Brad Delong worked under him, and Mickey Kaus likes to cite him as a great example of neoliberalism. Sumner is not equating "neoliberal" with right-wing, most of his shining examples are center-left governments (and I would add that Jimmy Carter deserves a lot of the credit normally assigned to Reagan for deregulation as well).

"Reagan, in particular had at least some actual policies that are conceptually inconsistent with neoliberalism"

I don't think Sumner included debt as an indicator of GDP, and he has argued against including size of government in economic freedom indices.

"Sumner's weak conceptual framework is further undermined his assumption that GDP growth is solely or primarily a function of the native degree of neoliberal policy implementation"

NO NO NO NO! That was the view he was arguing against! Krugman was suggesting that the higher growth rates before neoliberalism are a mark against it, Sumner responds that other factors (technology, I think) caused the change over time. So Sumner suggests that we compare countries because some of them had more neoliberal reforms than others, but all of them experiences the same change in time (they all "hit the wall" in the 70s).

"Let's agree on something"

Sumner most certainly does not agree, he is treating the whole period as neoliberal (though we did not reform as much as other countries did).

"Switzerland looks like the big loser here, Argentina holds its own after 1994, other changes are not particularly dramatic."

This is an area where catch-up growth is relevant: Switzerland was already rich, so (all else equal) we should expect poorer countries to grow faster.

Your conclusion places a lot of emphasis on the difference between post 1980 U.S presidents, but Sumner was never arguing about that.

TGGP -

I appreciate your looking at an old post and commenting so thoroughly.

Well, if you are correct -especially about Clinton and Delong - then I totally misread Sumner. I'll take some blame for that. But - perhaps his use of the word neoliberal to mean something other than the general definition I was able to track down has something to do with it.

I will still say, though, that focusing on 3 data points from a series of 29 - even if you have beginning , middle, and end - is a particularly obtuse way of looking at a data series.

Nor do I agree with your first item, that a data series represents a point. None of Sumner's countries have a monotonic GDP over time relationship, and exogenous and endogenous factors influence the results. One data point per year seems exactly right to me. Every data point is significant, and I think the shapes of the curves over time confirms that.

My point about ratios is that people commonly ignore the importance of the denominator. GDP/cap is a valid number, but one needs to be cautious when using it.

Thanks for your comments. I'll have another look at Sumner's posts.

Cheers!

JzB

Wow. Sumner strikes me as a smart guy, but your criticisms seem strong to me. I recall reading a couple of Krugman's posts on this, where he mentioned Sumner. I never read Sumner on this.

I liked the post. Your attention to ratios and the denominator problem is satisfying. The "GDP/cap isn't just a fraction" discussion was great. This may be the best line of all: "Most importantly, I believe in data-driven conclusions, not conclusion-driven data mining."

I think your "neo-liberal" link is all wrong about Adam Smith. I think Smith is misrepresented, as Keynes almost always is.

One big item: your "touchstone." You make much of declines in other nations during the Clinton years. For example, in the conclusion you write: "Fourth, nobody made a big gain vs Clinton..."

Also from your conclusion: "The point is that countries that did more reforms ... their biggest gains came against U.S. recessions..." I think that analysis is correct. Changes in U.S. economic performance appear on the graphs inverted, as changes in the economic performance of other nations.

I don't know about other nations but it seems likely that they all show declines in the Clinton years not because (by magic or coincidence) they all declined at the same time, but because the U.S. did exceptionally well in those years. And in fact the U.S. did exceptionally well in those years. (See The Real Economic Crisis. They refer to 1995-2004 as "reminiscent of the golden age.") So the declines the other countries show in the Clinton years simply reflect good years of the U.S. economy. It's the denominator problem.

Regarding the reasons for improved economic performance in the Clinton years, I had some thoughts on that in Another Piece of the Puzzle.

I have no thought on whether my comments support your position or Sumner's.

In response to TGGP's comment, Singapore also has increasing inequality -- according to Diary of A Singaporean Mind. (I can't find the particular post, though.)

I am agreeing that growth in US living standards slowed after 1973, and I am arguing that a great deal of this slow down occurred because of accumulating debt.

Oh, I left a comment here on the 10th but I don't see it. Maybe it got stuck in your spam filter. Anyhow, below is the afterthought I want to add:

Another thought. Your post concludes by noting that "growth in US living standards slowed after 1973," an important point that I think of as the failure of Keynesianism.

One might say that '73 was the end of a golden age, and that our economy never did really recover. If that is true, then the whole of Sumner's study is the study of a failed economy.

Intuition says more could be learned by comparing a failed economy to a golden one, then by what Sumner has done. His work is the ultimate in cherry-picking!

Art

Art -

It did get hung up in spam, mysteriously. First time that has ever happened.

I have to disagree on the failure of Keynesianism. As you can see here, after about 1968, Keynes was abandoned in the U.S. The failure period came with the all-deficits-all-the-time approach.

Cheers!

JzB

"Keynes was abandoned in the U.S. The failure period came with the all-deficits-all-the-time approach."

So Keynes was saying we should REDUCE debt? That is what I am saying also.

When talking about Keynes, I think the focus on debt, per se, is misplaced.

Keynes realized what conservative economists seem to deny, and that is that capitalism depends on spending. If the private sector doesn't provide the necessary spending, then the government comes in to take up the slack.

If private sector sending is adequate, the government can scale back spending. The resulting surpluses and deficits are outcomes, not goals. I guess the Keynesian budget goal was average balance - in the long run.

Cheers!

JzB

Post a Comment